Is PPAP Overkill or Essential? A Pragmatic Look at Automotive Quality

What PPAP Is Trying To Achieve (And Often Does)

What PPAP Is Trying To Achieve (And Often Does)

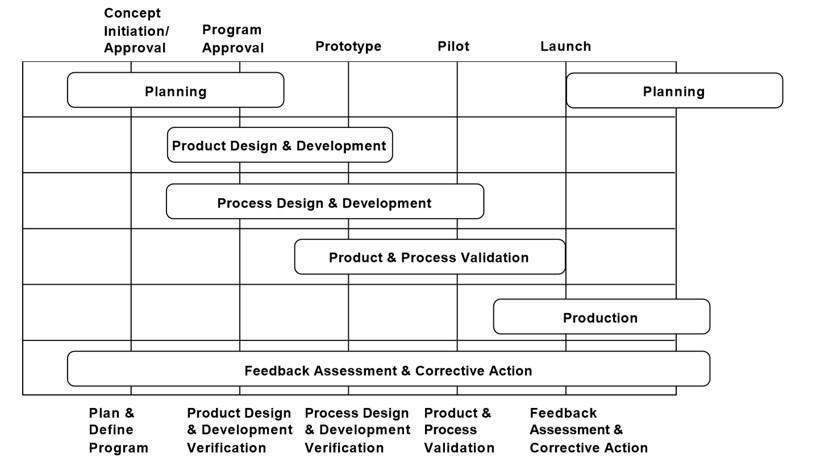

At its best, PPAP in manufacturing is a structured way to prove that a supplier’s process can repeatedly produce parts that meet all customer and regulatory requirements. The AIAG PPAP intent aligns with Ioan Feloniuk’s framing: demonstrate that design intent, process capability, and evidence are in place before ramping production. The origin of this post is at least in part from a linkedin post. The post is made by ioan Feloniuk.

The reason I say in part is that I have done some recent consulting at a company where I noticed a gap between a rational approach (APQP / PPAP) and something more haphazard. Part of the consulting was to demonstrate the training on the use of the PFMEA and the connection to the three levels of the control plan.

The core elements—DFMEA/PFMEA, control plan, MSA, capability studies, initial samples, and records of compliance—are not paperwork for its own sake; they are the backbone of a documented, analyzable process. When implemented thoughtfully, PPAP in manufacturing reduces launch chaos, improves first‑time‑right performance, and builds confidence between OEM and supplier.

The “Pro” Case: Why PPAP Still Matters

The “Pro” Case: Why PPAP Still Matters

From the pro‑PPAP angle, there are several strong arguments that echo themes in Feloniuk’s quality content. For the record, I am a big proponent of the APQP approach and the PPAP artifacts, though I also recognize there is no silver bullet when it comes to product development. With that said, the PPAP is a fairly comprehensive approach to delivering a quality product.

-

PPAP connects design and production

It forces the translation of drawings and specs into a real, frozen process with traceable controls, gages, and reaction plans, rather than assuming “the line will figure it out.” - PPAP is incremental, connecting development with manufacturing

Incremental manufactturing processses associated with incremental prototype and product iterations via the control plan. -

PPAP reduces quality and warranty risk

By validating processes up front, organizations identify potential failure modes and capability issues before they create field returns, line disruptions, or safety incidents. -

PPAP strengthens supplier relationships

A clear PPAP framework clarifies expectations, evidence, and acceptance criteria, thereby reducing friction by turning “quality” into shared, visible facts. -

PPAP supports audits and compliance

For IATF 16949 environments, PPAP in manufacturing is also part of the demonstrable system of planning, risk reduction, and evidence needed to satisfy customers, auditors, and regulators.

On this view, the question isn’t “why PPAP?” but “why would you bet millions in launch and warranty exposure without structured, evidence‑based approval?”

The “Con” Case: Where PPAP Becomes Wasteful

The criticisms of PPAP, including those raised implicitly in discussions around inefficiency and over‑processing, are not imaginary. Any approach can drift into a checklist mentality, which helps nothing and no one. During our time as process managers, we ensured the objective for each process element was known. Why we are doing this is important for all to know. Perhaps the process element does not apply. It is also true, as in my experience, that the inputs to any given process are seldom pristine or even the expected ones. This requires our team to determine how to achieve each process element’s objective, given these gaps. Which means our team will need to be engaged.

There are real ways PPAP in manufacturing can drift into pure bureaucracy.

-

Over‑processing and form‑filling

If the focus shifts from engineering insight to “completing all 18 elements no matter what,” PPAP devolves into template worship—lots of PDFs, little thinking. -

Duplicate or unnecessary PPAPs

Lean and PPAP specialists point to “overproduction” of PPAPs—running full submissions for low‑risk changes, or doing separate PPAPs where one well‑planned submission would suffice. -

Poor integration with day‑to‑day control

When PPAP documentation diverges from how the line actually runs, operators and engineers stop seeing it as a living control plan and treat it as an audit artifact. -

Slow response to engineering change

Rigid PPAP practices can delay change and tie up scarce quality resources, especially in high‑mix environments, leading to the perception that PPAP is blocking improvement rather than enabling it.

In short, when misapplied, PPAP can consume capacity, add lead time, and still fail to prevent problems—the worst of both worlds.

Reconciling Both Views: Risk‑Based, Evidence‑Focused PPAP

The way out of the pro‑versus‑con trap is to treat PPAP in manufacturing as a risk‑based framework, not a universal hammer. That aligns with modern interpretations of the core tools and with how many OEMs and suppliers are actually evolving their approaches.

-

Scale depth to risk

New products, safety‑critical items, high‑complexity or novel processes merit a full, deep PPAP; lower‑risk families or trivial changes may justify streamlined submissions or the use of existing evidence. -

Integrate PPAP with APQP and daily management

PPAP should be the culmination of APQP and robust launch activity, not an isolated paperwork event; when control plans, FMEAs, and capability indices are used on the floor, the PPAP package becomes a snapshot of reality, not fiction. -

Use digital tools and data

Rather than static documents, organizations can attach live SPC, MSA, and capability data to PPAP records, reducing manual effort and connecting approval to ongoing performance. -

Treat lessons learned as PPAP inputs

8D, warranty, and internal problem‑solving (such as the smartphone battery and tool frameworks highlighted in Feloniuk’s other posts) should explicitly feed into PFMEA and control plans so PPAP becomes a learning loop, not a one‑time gate.

This middle ground preserves the intent and benefits while addressing legitimate complaints about waste and rigidity.

A Practitioner’s Take: When PPAP Helps, When It Hurts

From a practitioner’s perspective, any comprehensive approach that closely connects development to the manufacturing line is beneficial. The PPAP offers this comprehensive approach and, as such, is a rational approach. None of this is going to work if we do not have a corporate culture that enables. In general, the PPAP and any rational approach will shine when it:

-

Is started early, as part of concept and process design, not thrown together days before a ship date.

-

Is co‑developed by cross‑functional teams—design, manufacturing, quality, and supplier—so it reflects real constraints and controls.

-

Is linked to actual metrics (scrap, rework, customer incidents) to prove its value or expose gaps.

It hurts when:

-

The team measures success in “number of PPAPs submitted” rather than defects avoided or stability achieved.

-

Quality engineers are buried in low‑value PPAP work while high‑risk launches lack depth and attention.

-

Data in PPAP is not maintained, so subsequent changes quietly invalidate the original evidence.

- The organization is more about the language than follow-through. When things get tough, they abandon the approach.

To continue the conversation, connect with us below.

For more information, contact us:

The Value Transformation LLC store.

Follow us on social media at:

Amazon Author Central https://www.amazon.com/-/e/B002A56N5E

Follow us on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jonmquigley/

https://www.linkedin.com/company/value-transformation-llc

Follow us on Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=dAApL1kAAAAJ