APQP Testing Limitations in Real-World Manufacturing

APQP Testing Limitations in Automotive and Manufacturing Quality

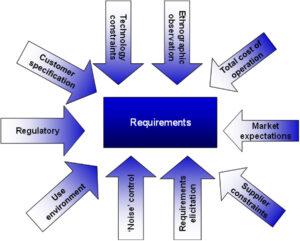

Advanced Product Quality Planning promises robust launches, but APQP testing limitations often emerge when teams equate “meets spec” with “fit for use.” APQP testing limitations become most evident when products pass all defined tests yet still fail in customer applications, field use, or long-term durability.

The root cause is often a narrow “test to specification” mindset, where verification focuses on document compliance rather than real operating conditions, system interactions, and manufacturing process variability. APQP testing limitations can be reduced, but not eliminated, by integrating better supplier selection, PFMEA, and process metrics into the development flow.

Limits of Testing to Specifications

Relying solely on “meets specification” testing has several inherent limits:

Relying solely on “meets specification” testing has several inherent limits:

-

Specifications rarely capture full use conditions, such as misuse, abuse, and edge cases, that customers still expect the product to survive.

-

Testing to nominal values can ignore tolerance stack-ups, environmental extremes, and duty cycles that actually drive field failures.

-

Static specifications cannot keep pace with evolving customer expectations, regulatory changes, or new use cases over the product’s life.

-

Late-stage testing only reveals failures; it does not inherently prevent them, and fixes at this point are expensive and disruptive to launch.

This is why APQP testing limitations must be addressed upstream, through risk‑based planning rather than heavier final inspection or more of the same specification-based tests.

Supplier Selection Methods That Reduce Risk

Effective supplier selection is one of the most powerful levers to mitigate APQP testing limitations before they appear:

-

Use structured criteria: technical capability, process robustness, quality system maturity, APQP experience, PPAP performance, and responsiveness to corrective action.

-

Evaluate historical performance: delivery, defect trends, containment effectiveness, and the ability to sustain improvements, not just short‑term fixes.

-

Assess manufacturing and test capability on site: special processes, calibration, gage R&R, in‑process controls, and evidence of disciplined problem solving.

-

Apply weighted scoring and multi‑disciplinary reviews so purchasing, engineering, and quality jointly own supplier decisions.

When suppliers are selected based on process capability and learning behavior, rather than just price, downstream testing finds fewer surprises and fewer late failures.

APQP, PFMEA, and Manufacturing Process Design

-

Process Flow Diagram: maps each step where the part can fail, framing PFMEA analysis around real operations and handoffs.

-

PFMEA: identifies failure modes, causes, and effects at each step, with severity, occurrence, and detection guiding where to invest prevention and controls.

-

Control Plan: translates PFMEA actions into concrete controls, inspection methods, and reaction plans at the line.

This upstream work attacks APQP testing limitations by making the process itself less likely to create failure conditions. Instead of trusting test results alone, the team designs manufacturing to be capable, stable, and measurable.

Control Plans and Monitoring Supplier Maturity During Line Development

A control plan should start as a living hypothesis about how the supplier will control key product and process characteristics, then mature as the line design, PFMEA, and trials progress. Early in development, you are validating assumptions; by SOP, you are confirming that the supplier’s process consistently meets capability, stability, and reaction-time expectations.

During line development, monitor the supplier’s control plan’s growth along three dimensions: structure, evidence, and behavior. Structurally, the plan should stay aligned with the latest process flow and PFMEA, with clear linkages between high‑risk steps and specific controls (error‑proofing, checks, reaction plans). Evidentially, entries that were initially “TBD” or qualitative should be replaced with real data from MSA, capability studies, trial builds, and pre‑launch runs. Behaviorally, you should see the supplier using the control plan as a day‑to‑day management tool: updating it after lessons learned, triggering reactions when data goes out of control, and using it in layered process audits.

Control Plan Levels

Practically, you can track maturity with a simple staged view across the program timeline. Heavy involvement with the supplier as the manufacturing line is being developed goes a long way to ensuring the manufacturing line and as a consequence, the products from the manufacturing line are competent.

Level 1 – Prototype Control Plan

Purpose: Control during early development and learning

When used:

-

Prototype builds

-

Pilot runs

-

Early design validation

Characteristics:

-

Focused on learning and discovery

-

Controls may be temporary or experimental

-

Heavy inspection and testing

-

Data collection to understand process capability

-

Frequent changes expected

Goal:

👉 Identify risks, unknowns, and design/process weaknesses before launch

Level 2 – Pre-Launch Control Plan

Purpose: Control during process validation and ramp-up

When used:

-

Pre-production

-

Process validation (e.g., PPAP runs)

-

Early customer shipments

Characteristics:

-

Tighter controls than production

-

Increased inspection and monitoring

-

Additional checks for high-risk steps

-

Reaction plans are well defined

-

Controls reflect known risks from FMEA

Goal:

👉 Ensure the process is capable and stable before full production

-

Prototype phase: rough control plan aligned to the draft process, high‑risk characteristics identified, basic checks defined.

-

Pre‑launch phase: control methods defined for all critical and significant characteristics, MSA completed on key gages, initial capability data available from trial builds.

-

Production phase: full reaction plans in place, control limits established and used, periodic review of scrap, FPY, and customer issues, with feedback feeding into control plan updates.

Level 3 – Production Control Plan

Purpose: Ongoing control of a stable process

When used:

-

Full production

-

Normal operations

Characteristics:

-

Optimized, efficient controls

-

Focus on prevention, not detection

-

Statistical process control (SPC), where applicable

-

Standard work is fully defined

-

Continuous improvement is built in

Goal:

👉 Maintain quality, minimize variation, and sustain performance over time

Gate reviews and supplier APQP checklists should explicitly ask, “What changed in the control plan since the last review, and what data supports those changes?” That question makes the growth of the control plan visible, pushes the supplier to systematically close gaps, and reinforces that the document is not created to satisfy a customer template but to run and continuously improve the line.

Tools and Metrics Beyond “Pass/Fail”

Tools and Metrics Beyond “Pass/Fail”

To move beyond simple “pass/fail to spec” thinking, the manufacturing organization needs a richer tool and metric set:

-

Capability indices: Cp, Cpk, Pp, Ppk on critical and significant characteristics to quantify how well the process fits the tolerance.

-

Measurement Systems Analysis: gage R&R, bias, linearity, and stability to ensure data used for decisions is trustworthy.

-

In‑process performance: first‑pass yield, scrap rate, rework rate, and defects per million opportunities across the process flow.

-

Reliability and validation: accelerated life testing, environmental stress, and usage‑profile‑based test plans informed by DFMEA and field data.

-

Supplier metrics: on‑time PPAP, containment frequency, effectiveness of corrective actions, and trend in systemic improvements.

These tools and metrics extend insight far beyond the limitations of APQP testing, showing how robust the system truly is rather than just confirming that one batch met the drawing.

Using Data to Close the Loop

Finally, even the best APQP, PFMEA, and specification-based testing will miss some risks without a closed feedback loop:

-

Feed warranty data, field returns, and customer complaints directly into DFMEA and PFMEA updates.

-

Revisit specifications and validation plans when recurring failure modes appear, instead of adding one‑off tests with no systemic change.

-

Use structured problem‑solving (8D, A3, fishbone, 5‑Why) to drive permanent changes to design, process, or supplier capability.

By treating testing as one element of a risk‑based system rather than the final safety net, organizations can control APQP testing limitations and deliver more reliable products at launch and over the life cycle.

For more information, contact us:

The Value Transformation LLC store.

Follow us on social media at:

Amazon Author Central https://www.amazon.com/-/e/B002A56N5E

Follow us on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jonmquigley/

https://www.linkedin.com/company/value-transformation-llc

Follow us on Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=dAApL1kAAAAJ