Its been Five Weeks

A Song

As I wrote this, I kept getting that song by Barenaked Ladies, One Week, going through my head. I have been working on the bassline for that song. My kid introduced the song to me some years back and just recently I thought about learning it. I’m very close.

Estimating

I have a question for all of you project managers out there.

Are you part of the cost (time and material) and delivery date estimating process, or are those numbers handed down to you from another individual?

I have been responsible for the estimates for most of my project management career. That is not to say that I estimated the project. I worked with the team responsible for the project to generate the estimates. We would sometimes produce a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) for the effort, but not always. We would always ask questions, discovering underlying assumptions. Generally, the work’s people are better positioned to estimate what is required. Even when the team members are not so skilled in their participation, this exploration and estimating are opportunities for learning and developing team member skills.

The Role of Questions

I was the process manager at a vehicle OEM. The managers were responsible for technical areas, such as systems engineering, embedded components, hardware, and wire harnesses. As projects came into the department, the department managers would evaluate the project scope and provide the initial estimate of their portion of the effort. One project came in for this management estimate. The systems engineering manager blurted out the hours he believed required to perform the systems engineering work, specifically to write the system’s specifications. I asked the manager, “How many system-level specifications would be required to be written or updated.” He reviewed the list, and we did the top-level math, illustrating that he had grossly underestimated the work.

Why the question

I have recently seen a project that the sales department estimated. The work areas ranged from designing mechanical equipment and interfaces to existing equipment to software (for components not used before by the team members), safety interlocks, and PLC manipulation of the system. The total time estimate for the work is 200 hours. Given the work scope, a quick look at the hours seemed errant. When I approached the managers with the lead manager, I asked if all of this could be accomplished in 5 man-weeks.

5 Man Weeks

Some around the table did not seem understand this concept well. I will describe it here. A man week is usually 40 hours, so 200 hours would be 200/40, which is 5 man weeks. This essentially says one person working for 5 weeks could accomplish the goal of this project, that is if one person had all of the requisite skills. I never use 40-hour work week for team members’ available hours. This is seldom an accurate workweek availability number, I usually use 32 hours unless there are special circumstances. However, for this exercise, let’s be optimistic. For example, the skill list for this example is listed below, and if we divide the hours 200, by the 11 activities, we end up with about 18 hours per activity below.

- Manufacturing equipment design

- Parts ordering and kitting

- PLC control design

- PLC programming

- Design review and system updates

- System documentation

- C program

- System assembly

- Testing and verification

- Corrective actions (defects)

- Install at customer

Progress

As the work progressed, the top manager was informed of the progress, and the response was always, “This project is taking too long.” Just passed the design review with customer approval, “why is this taking too long.” When attempting to put the project into Gantt chart form, the manager informed the project manager not to waste time on creating such. “How would anybody know what is too late“? This is especially true when we have limited or no mechanism for assessing the spending rates against the Gantt chart progress (Earned Value Management or something like that). This is where we should differentiate the work hours from the project’s duration.

Duration and Time

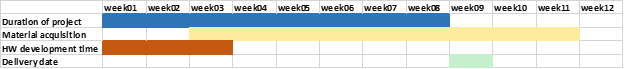

The project’s duration was fixed at 8 weeks in the mind of the top-level manager, the expected time to deliver the product to the customer. These 8 weeks the hours to deliver were estimated at 200. Things get a little weird here, as the material acquisition and delivery took over 9 weeks. So, the delivery to the customer was to be in 8 weeks, but the constituent parts would not be received until a week later. There is no assembly time, no software development on the system, and no verification and testing possible. As you see from the rough schedule below, we would need to start the product design before the project start date by about 4 weeks to meet the project schedule.

Consequences

Should the project manager be held accountable for delivery dates and cost estimates from those outside the team doing the work? From my perspective, I would work toward this expectation, but the team would:

- Ensure those who estimated the effort would know the progress (find metrics).

- Not be held accountable for the project results compared to cost estimates and delivery date.

Perhaps more importantly, when the project manager reported actual progress, their response was “it is taking way too long.”

Responsibility and Accountability

Of course, management may need to provide estimates along with the basis. I prefer to derive estimates from the bottom up, with the scope originating from management or sales personnel. The reason for that preference is that those who do the work should be closest to the work and know what is required to do the work in time and tools. I believe the project manager should be responsible for developing these estimates, with the responsibility of the estimated content from those subject matter experts (SME). This team will be responsible for meeting the customer’s objectives, working through constraints, and more. If you hand the team the estimates, especially if the team believes these estimates are in error, the team will likely feel little accountability for meeting those estimates. I would not feel obliged to meet somebody else’s estimates if I believed those estimates in error.

Conclusion

Some things may improve the outcome of these types of estimating on the project results. Sometimes, those doing the work may lack the experience or training to provide adequate estimates. The problem is, that when others than the team provide the estimates, we are usurping their learning opportunity. We essentially reinforce keeping our team at the present competency level.

- If you are handling the estimates for the project team, do not assume there is a commitment to those estimates from the team members – very likely, you do not. At a bare minimum, you should consider providing the rationale for those estimates.

- All estimates are hopefully educated guesses, but guesses nonetheless. It is essential to measure while working to assess how close our assessments might be to actual. We can take necessary actions, reduce scope, alter time and cost estimates, or even kill the project. Respond appropriately if you see the calculations are not accurate.

- Don’t forget the measurements. Even when we impose the estimates, or perhaps especially, we should be taking measurements and be receptive to the idea that our estimates are not entirely accurate (see item 2). This ability to accept things as they are and adapt, in our experience, adds to credibility. Moreover, this adds to understanding the true business case and benefits of the project. Updating the